As Vapouround readers will know, the Tobacco and Vapes Bill – which at the time of writing had reached committee stage in the House of Commons after passing successfully through two readings – includes some important provisions on vape flavours.

It doesn’t ban them, but it gives the government power to issue regulations about flavours in tobacco and nicotine products, and it’s a pretty safe bet that any such regulations would take the form of restrictions on flavour availability.

The industry and consumers alike will hope that they fall well short of a total ban leaving only tobacco-flavoured products legal, and fortunately, that’s not an unreasonable hope.

Despite the UK government’s recent push to regulate vaping more tightly, it does still seem to acknowledge the harm-reduction argument for the products, and ought to be (at least in principle) receptive to the idea that some non-tobacco flavours are legitimately necessary to move existing smokers to vapour.

If so, the question is where the line would be drawn, indeed how the line would be defined: making a clear-cut distinction between flavours primarily aimed at kids and those significantly appealing to adults is not easy.

What happens when governments ban vape flavours?

What happens if you do ban flavours totally (or near-totally), though? My ECigIntelligence colleague Pablo Cano Trilla delivered a fascinating presentation around this topic at the E-Cigarette Summit in London in early December, and it’s worth considering some of the key points that arose.

First of all, draconian flavour bans are not currently as common as you might think. Of a hundred countries that we studied at ECigIntelligence, 62% allow flavours; 9% restrict them; and only 11% ban them outright. (The remaining countries, just under 20%, prohibit vapes altogether so the question of flavours is academic in them.)

On the surface, this might seem to suggest that flavour restrictions are not in fact a popular policy option, and that anyone worried about the implications of the Tobacco and Vapes Bill in that regard can breathe easy. This would, however, be naïve: because, while it’s true that only a small minority of countries currently ban flavours, the level of talk about doing so seems at times to verge on the deafening.

In Europe alone, for example, recent proposals have arisen in Ireland, Slovakia, Poland and Spain (the Czech Republic providing a very rare case in contrast, of a country which planned to enact a wide-reaching flavour ban and then pulled back from the idea at the last moment, instead prohibiting only “candy”-type flavours). And of course there is the possibility of an EU-wide ban in the next incarnation of the Tobacco Products Directive (TPD), which may appear in 2025.

So, as Pablo pointed out, while only 20% of the countries we studied currently had flavour bans in place, check back in a couple of years and the number is likely to be much higher.

How effective are vape flavour bans?

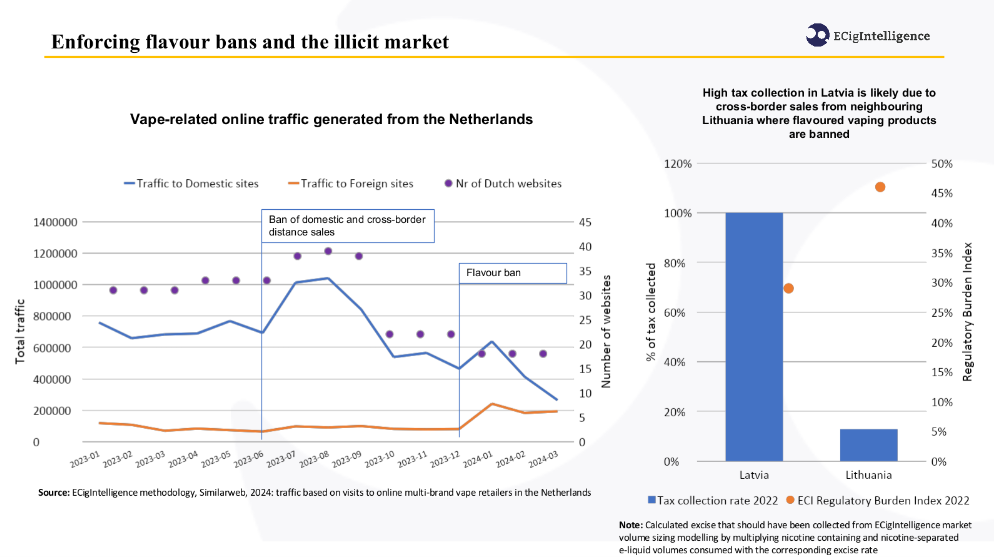

Do the bans work? Much evidence suggests not. One of Pablo’s charts, reproduced below, shows how online traffic from the Netherlands to websites selling vape products in other countries increased sharply as soon as the Dutch flavour ban came into force.

Another shows how Latvia (where flavours are not banned) collects far more tax from e-cigarette products than neighbouring Lithuania (where they are), despite having a smaller population. In both cases the implication is clear – consumers in the Netherlands and Lithuania faced with a flavour ban simply started buying flavoured products abroad.

To be fair to the prohibitionists, it might be argued that these international shoppers were more likely adults than kids, in which case the bans might have at least partially achieved their objectives. And of course it could also be pointed out that – because of both Brexit and geography – the UK’s borders are somewhat easier to control than those within the EU anyway.

However, this also raises the possibility that instead of turning to legal markets in other countries, British vapers who want flavours would simply resort to an illicit market within the UK…and in that case, the customers of illicit sellers surely would include many underage users, too.

There are other reasons to doubt that flavour bans are a fully-fledged success. A 2020 Danish Health Authority study, for instance, found that a flavour ban led to a rise in smoking among young people. In Ireland, a survey conducted earlier this year found that one in five ex-smokers who vape would return to combustible cigarettes if flavoured vapes were banned. Unintended outcomes like these, as well as the strong likelihood of fuelling the illicit market, are reasons to fervently hope that whatever restrictions may be enacted as a result of the Tobacco and Vapes Bill, they are thought through carefully.

Discover more industry insights from EcigIntelligence

Enjoyed reading this article? Read some of EcigIntelligence’s other exclusive pieces published by Vapouround including The Latest Analysis on Vaping Hardware in the UK and Is the Rise in Nicotine Pouch Sales a Cause of Concern for the UK Vape Sector?